Methods

Session: Poster Session B

(179) Excluding or Censoring on Mediators and the Resulting Causal Estimands: An Example of Hormonal Contraceptives and Venous Thromboembolism Risk

Tuesday, August 27, 2024

8:00 AM - 6:00 PM CEST

Location: Convention Hall II

Samantha Shapiro, MSc

PhD Candidate

McGill University, Canada.jpg)

Michael Andrew Webster-Clark, PharmD, PhD (he/him/his)

Assistant Professor

McGill University

McGill University

Montreal, Canada

Presenting Author(s)

Co-Author(s)

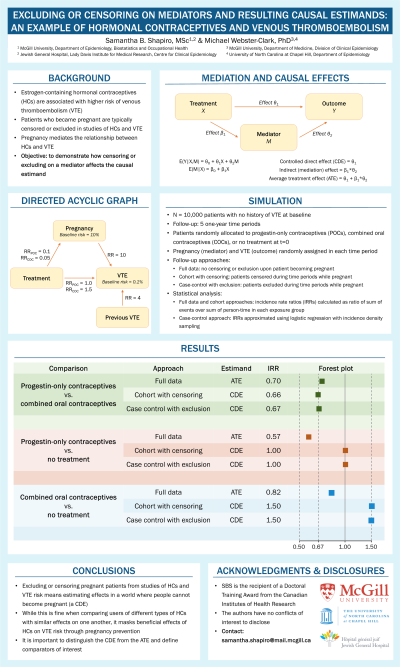

Background: Decades of case-control and cohort studies have established that estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives are associated with higher risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Typically, patients who become pregnant are excluded (in case-control studies) or censored (in cohort studies). To date, little attention has been paid to the fact that this results in study estimating the controlled direct effect (CDE) and how the resulting quantity differs from population average treatment effects (ATE) for specific comparators.

Objectives: Explore the difference between the CDE and the ATE when comparing progestin-only contraceptives, estrogen-containing oral contraceptives, and non-use of contraceptives with data simulated from known associations between contraceptive use, pregnancy, and VTE.

Methods: We simulated a 10,000,000 patient randomized trial assigning patients to one of three regimens: 1) a treatment that greatly decreased the probability of pregnancy but had no direct effect on VTE (progestin-only contraceptives (POCs)), and 2) a treatment that decreased the probability of pregnancy slightly more but increased the relative risk for VTE in non-pregnant patients by 1.5 times (combination oral contraceptives (COCs)), and 3) nothing. Pregnancy increased the risk of VTE by approximately 10 times. We simulated 5 “years” of follow-up, with some patients becoming pregnant at the start of each year and follow-up stopping after a VTE. For each comparison, we compared A) incidence rate ratios for VTE using the full data to B) the incidence rate ratio estimated by a cohort study that censored pregnant individuals and C) the odds ratio from a case-control study that excluded pregnant cases and controls.

Results: When comparing POCs to COCs, incidence rate ratios were similar using all three analytic approaches (full data IRR: 0.70, censored cohort IRR: 0.67, case-control OR: 0.67). When comparing either to no treatment, however, IRRs differed greatly. For POCs, the full data IRR was protective while others were null (full data IRR: 0.57, censored cohort IRR: 1.00, case-control OR: 1.00); for COCs, the full data IRR was protective but others were harmful (full data IRR: 0.82, censored cohort IRR: 1.50, case-control OR: 1.50).

Conclusions: Excluding or censoring pregnant patients from studies of contraceptive VTE risk means estimating effects in a world where people cannot become pregnant (a CDE). While this is fine when comparing users of different types of hormonal contraception with similar effects on one another, it masks beneficial effects of hormonal contraception on VTE risk through pregnancy prevention. It is important to distinguish the CDE from the ATE and define comparators of interest.

Objectives: Explore the difference between the CDE and the ATE when comparing progestin-only contraceptives, estrogen-containing oral contraceptives, and non-use of contraceptives with data simulated from known associations between contraceptive use, pregnancy, and VTE.

Methods: We simulated a 10,000,000 patient randomized trial assigning patients to one of three regimens: 1) a treatment that greatly decreased the probability of pregnancy but had no direct effect on VTE (progestin-only contraceptives (POCs)), and 2) a treatment that decreased the probability of pregnancy slightly more but increased the relative risk for VTE in non-pregnant patients by 1.5 times (combination oral contraceptives (COCs)), and 3) nothing. Pregnancy increased the risk of VTE by approximately 10 times. We simulated 5 “years” of follow-up, with some patients becoming pregnant at the start of each year and follow-up stopping after a VTE. For each comparison, we compared A) incidence rate ratios for VTE using the full data to B) the incidence rate ratio estimated by a cohort study that censored pregnant individuals and C) the odds ratio from a case-control study that excluded pregnant cases and controls.

Results: When comparing POCs to COCs, incidence rate ratios were similar using all three analytic approaches (full data IRR: 0.70, censored cohort IRR: 0.67, case-control OR: 0.67). When comparing either to no treatment, however, IRRs differed greatly. For POCs, the full data IRR was protective while others were null (full data IRR: 0.57, censored cohort IRR: 1.00, case-control OR: 1.00); for COCs, the full data IRR was protective but others were harmful (full data IRR: 0.82, censored cohort IRR: 1.50, case-control OR: 1.50).

Conclusions: Excluding or censoring pregnant patients from studies of contraceptive VTE risk means estimating effects in a world where people cannot become pregnant (a CDE). While this is fine when comparing users of different types of hormonal contraception with similar effects on one another, it masks beneficial effects of hormonal contraception on VTE risk through pregnancy prevention. It is important to distinguish the CDE from the ATE and define comparators of interest.